There’s a lot of work to be done on my embryonic farm and it all begins with taming a troublesome mess of briars, trees, and rocks.

But a question occasionally comes to mind to anyone clearing land: How did our pioneer forefathers transform countless acres of virgin forestland into working farms?

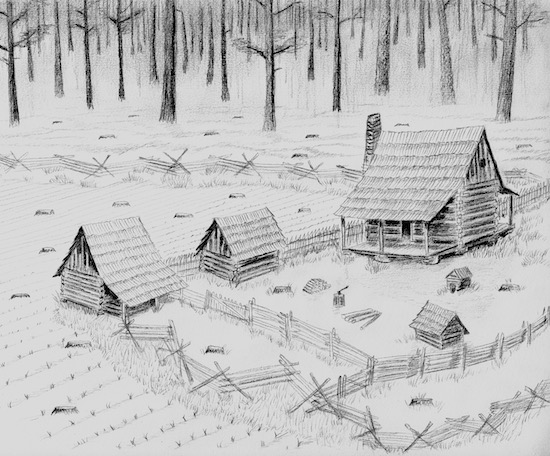

Well most of what they encountered back then…we rarely even see anymore. In my area of Arkansas, early 19th century settlers arrived to find an old-growth pine forest thats growth cycle had been continued uninterrupted for decades on end. What does that mean? I’ll tell you: It means big tall pines, spaced well apart, with little undergrowth. But in these modern times, with most of the country having been harvested and replanted several times over, relatively short growth cycles with many young trees and much undergrowth—messy tangled undergrowth—are what we’re use to seeing.

Around 180 years ago, cutting 16 to 20 mature virgin pines might have yielded the diligent farmer about an acre of cleared ground. About ten cleared acres was probably typical for the first year’s crop. He just dodged the stumps with his plow for a few years while growing crops all around ’em. Then he and his team could pull them out, roots and all, after they’d had time to rot. This process was repeated until the farm was as big as need be.

Don’t get me wrong…clearing land was still back-breaking work back then, it just usually wasn’t the tangled mess we’re accustomed to. But when cleared land is allowed to revert back to its original state, it becomes chaotic for the first few decades. A real briar patch of a mess.

But God can clean this mess up using time, and the same principles of nature that made the mess to begin with: The bigger the trees grow, the less sunlight that falls under ’em, the less brush and undergrowth that grows beneath ’em. Over time, this causes the remaining trees to grow very large, very tall, less knotty, and pretty far apart from each other. What intentional and brilliant logic there is in creation!

Although part of my property’s already been cleared it’s time to do more, and I start with the big stuff first. With a chainsaw I cut trees on future garden spots much higher than normal…about head high; then use the extra leverage of the tall stump to pull them out with the tractor after they’ve rotted a few years. In the meantime, I can plow or till around ‘em if need be. Sometimes, though, just loppin’ the top off like this won’t kill the tree. You’ll also need to girdle it. What’s that? I’ll tell you.

You “girdle” a tree by scoring the bark off its entire circumference with an axe. It’s simply denying its flow of moisture or sap. This is an old practice farmers used that killed trees, allowing sunlight to reach crops as the tree rotted upright. Pine logging companies in this area also used to do this to hardwoods so that the pines would gain the upper hand. My own Pa Mac (grandpa) and an uncle were once part of a girdling crew many years ago.

Now that I’ve got some trees layin’ around, I believe I’ll decide how they’ll be used.

The straightest, knot-free logs can be used for making lumber with my chainsaw and Alaskan Mark III chainsaw mill attachment made by Granberg International. These premium pine logs can also be “rived” or split into thin boards for roofing called “shakes” (a lot cheaper roofing material than tin). I can also save the best hardwood logs for tool handles or wooden pitchfork making (we’ll save that topic for another day).

Cedar logs are valuable for building pole barns. Their built-in resistance to rot or termite damage also makes ’em good fence posts.

The limbs and logs of knotty hardwood tops make good firewood. After that, the smaller branches and limbs can be piled up and burned on unwanted stumps, or on future garden spots since ashes can sweeten up acidic pine forest soil.

Brush, fence posts, and even logs can be pulled by SUV’s, ATV’s, trucks, tractors, horses…or even a pair of yoked steers like these I had a few years back.

To burn a stump out I dig down as much as possible around it, then build a sizable brushfire over it. Sometimes this takes several attempts in order to burn down below where my plow or tiller will dig.

Smaller stumps, trees, or brush can be burned down as far as possible or pulled completely out with a truck, team of horses, tractor…or anything with enough power for the job. If I’m clearing land that will be used for pasture, I cut the tree as low to the ground as possible. Then with a little bit of patience and skill (and a chainsaw) I trim and bevel the edges of the stump to make it knobby and rounded, and easily passed over later by a swing blade, brush blade, scythe, or mower.

I’m also piling up larger rocks as I’m clearing.

They’re categorized by their shape into different piles according to their future use: Good brick-shaped rocks for foundation stones, rock with at least one flat side for a stone floor in the workshop, others for small retaining walls in sloping gardens or raised beds, and the odd-shaped ones for stacking around the chicken coop to keep critters out.

Long ago, homemade sleds were pulled by draft animals to move rocks as well as hay or firewood. Think I’ll make something like this.

But for now an old truck hood is doing the trick.

Pictures and article by Pa Mac, copyright 2012