To cook my beans and keep me warm,

I’ll mud and cat all day

But if at night I hear the roar,

I’ll kick the pole, then run away.

– Clay Dobbins

From a quarter of the year to almost half of it, most of us in the United States are trying to keep warm…somehow; always been that way. I prefer summer over winter for this very reason alone: You have to spend either energy or money, or both–to keep warm in winter; but to stay cool in summer the shade trees and creeks are free and easy.

Staying warm the coming winter was foremost on the mind of our pioneering ancestors as they were first building their homes in the warmer months. And before the cast iron stoves were increasingly available and affordable, the fireplace and chimney were used for cooking as well as relief from uncomfortably low temperatures. But how did they use to build a fireplace and chimney if no bricks or no mortar (and sometimes no stones) were available?

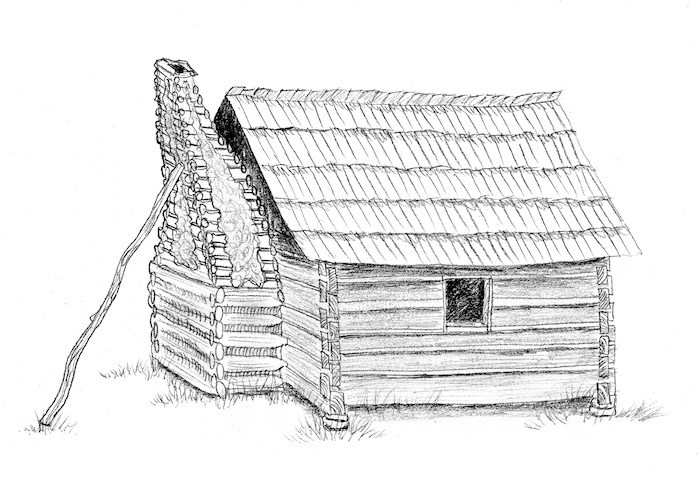

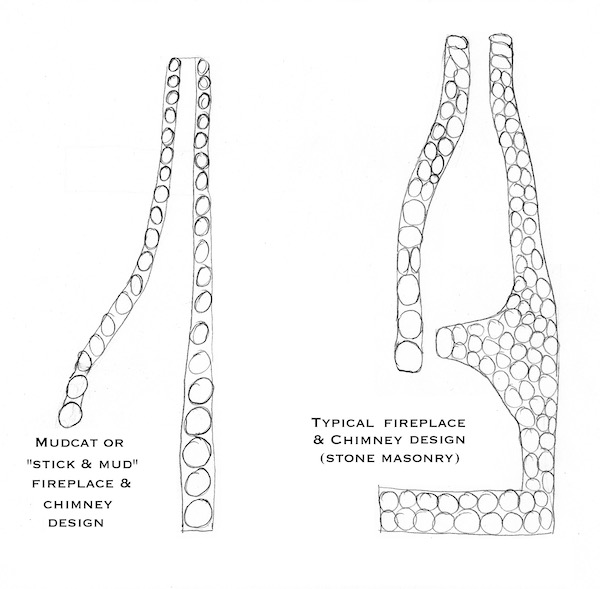

The simple solution was a fairly common type of fireplace occasionally known by a rather odd name: the “mudcat” chimney. That’s my favorite nickname for it, although it was sometimes simply called a “cat” chimney, or “stick and mud” chimney (the latter actually describing it best for what it was…sticks and mud). In the area where I live, finding large field stones for building is no problem; and often rocks were used to build entire chimneys. But for the traditional farmer whose giftings may not have included masonry (not to mention the unavailability of lime or conventional mortar), a wood and mud fireplace and chimney would have been just the thing for many. Where large stones were available, the firebox (the bottom part where the fire goes) and hearth was sometimes masonry built, to a height of about 4 or 5 feet, with a stick and mud chimney rising from there on up.

In many parts of our country where no large rocks or any rocks at all are prevalent, the mud and sticks (or small logs) comprised the firebox as well. Earlier on, these sticks were simply round poles from small trees notched to receive each other much like the log walls of the home. Later on, sticks were ripped from milled lumber and sometimes nailed to a vertical pole framework that supported the whole. Mud or clay “chinking” was used to make the heated parts of the structure fireproof, and was generally the same materials that the cracks between the logs of the house’s walls were filled in with. The mud was typically the best clay as could be locally found, often mixed with the choice of a number of things that served to hold the clay together until the fire dried and hardened it. The materials used for this “reinforcing medium” were dictated by what was most accessible…and probably laying or growing within a rocks throw of the whole operation: hay (probably old), straw, dried weeds, horse hair, human hair, old rope…and maybe a combination of all of these and then some (the sky’s the limit when you’re farming or homesteading). After proper mixing, the mud chinking would be rolled out in long pieces. These oblong rolls of pliable clay were called “cats” and were set on top of a horizontal stick or log, then mashed down by the next stick, and so on. The extra mud that squeezed out from between the two would be flattened and smoothed across both, probably using water to keep it moist as you worked. The outside could be smoothed or not; I’ve seen ‘em both ways.

The firebox, where most of the intense heat would be, needed much extra mud lining for obvious reasons (probably at least 6 inches or more, that is, if the firebox was not made of stone). The penning of the logs that made up a firebox were also not notched in permanently with the wall logs, because it was a given that they would need to be replaced in a few years. Instead, they were attached to vertical wooden supports or just tapered and fit to rest freely between individual wall logs. It likely would not have been difficult to pull the whole thing away from the house should it catch fire or need replacing. Just keep the dogs and kids away when you start pullin’.

In most chimneys, the inside of the flue just above the firebox must be built a certain way as to “draw” the air upwards. This is done with two main (often competing) goals in mind: Letting most of the smoke leave the house, while making most of the heat stay…now that’s quite the trick. The shape of the “throat” (the opening just above the firebox) and the area above and to the back of it had a lot to do with that. There were a couple of rule of thumbs to good normal flue design: One was making the space above and behind the throat larger than the opening of the throat itself, and the other was making sure that opening at the top of the chimney was not smaller than the opening of the throat. This was all made doubly difficult for the pure mudcat builder who couldn’t build a masonry throat with slanting inner walls and shelves. The mudcat firebox was more or less vertical “up and out”. However, the higher above the roofline a flue extends helps it catch passing wind better, thereby creating a draw or natural draft up the chimney. Sometimes the mudcatter probably hit on a good design…and sometimes he didn’t, to the dismay of his wife who was left to cook over an often smoky fireplace.

As with most things on the farm, the design of the entire fireplace and chimney was left to imagination, availability of materials, and ability. There were as many types or variations of a stick and mud chimney/fireplace as there were builders or availability of materials.

Several vintage photographs of houses with mudcat chimneys show long poles supporting leaning chimneys. I originally thought these to be quick and easy efforts to keep them from falling. That may have been. Sometimes poorly built firebox foundations would give to one side or the other causing the whole structure to lean; but it’s a fact that many of them were built with a taper away from the upper wall of the house to begin with; a built-in lean. Toward the top the thinner, mud-lined sticks of the increasingly narrow flue are more vulnerable to deterioration…and therefore subject to starting dangerous house fires. This deterioration of the mud from rainfall was even hastened without the protection of an overhanging gable to keep the structure somewhat dry. In addition to using the poles to pry the burning chimney away from the house and down onto the ground in the event of a fire, I believe that the supporting poles would just have been kicked loose allowing a dangerously burning flue to fall on its own. Kicking a pole would just about be all I could coherently think to do if awakened in the night by the roaring sound of a burning flue. Did I mention that these mudcat chimneys required a lot of careful attention and maintenance to avoid danger from catching on fire? Well, they did; but that’s just one of the manifold items of attention that added to the farmer/settler’s list of running the homestead. The fact is, they were probably just a tad less trouble to build than to maintain safely.

Now here’s a plain truth: There are fewer and fewer traditionally built log homes from the settler era that exist today. The reason for this (I theorize) being that the typical farmer did not build his home with endurance as the number one priority (given the carpentry skill level of the average farmer), but for expediency, i.e., getting it built quick, getting in it, and then getting to the farm work. I would suppose that there are far fewer mudcat chimneys for the same reasons plus some, given their fragile ability to endure weather. In fact, I never even entertained the thought that any still existed in my area until…

…one Sunday while taking a slightly different route home from church, I happened to look over in a field where an old log house stood that was now being used only as a barn/shelter for cattle. At the end of the house I recognized something I had only scene in old photographs: an old time, mudcat chimney.

I returned later, camera in hand to find the owner tending his cattle. He very graciously (yet with some small bewilderment) allowed me to get my fill of pictures of the old stick and mud chimney.

This particular version that I found was built probably about a generation after the settler era.

At some point in recent history, the flue had been wired to the main part of the house with a cable in an effort to preserve it and delay its inevitable fall.

Inside the flue; completely lined with smoothed over clay

The firebox on this one had been lined with field stone, but had crumbled with many of the stones missing for whatever reason. Note the bent iron tire from a wagon wheel (inside the firebox) that had been used to support the inside upper arch or opening of the firebox.

The sticks were of milled pine lumber, nailed to a vertical framework.

The chinking was apparently indigenous clay mixed with some type of local grass or weed, and probably slaked lime, given that it was of later construction.

Article, drawings, and photographs by Pa Mac

Copyright 2013, Caddo Heritage Productions